-

Find in Members

Find in Members Find in Projects

Find in Projects Find in Channels

Find in Channels

Build the technology of the future. Protect the nation from attack. Buy a sports car.

These were some of the rewards of working in the semiconductor industry, 200 high school students learned at a recent daylong recruiting event for one of Taiwan’s top engineering schools.

“Taiwan doesn’t have many natural resources,” Morris Ker, the chair of the newly created microelectronics department at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University told the students. “You are Taiwan’s high-quality ‘brain mine.’ You must not waste the intelligence given to you.”

The island of 23 million people produces nearly one-fifth of the world’s semiconductors, microchips that power just about everything — home appliances, cars, smartphones and more. Furthermore, Taiwan specializes in the smallest, most advanced processors, accounting for 69% of global production in 2022, according to the Semiconductor Industry Assn. and the Boston Consulting Group.

But a pandemic-induced chip shortage, along with rising geopolitical tensions in Asia, have highlighted the fragility of the current supply chain — and its reliance on an island under the specter of a takeover by China.

Across the U.S., Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China, the semiconductor industry is already short hundreds of thousands of workers. In 2022, the consulting and financial services giant Deloitte estimated that semiconductor companies would need more than 1 million additional skilled workers by 2030.

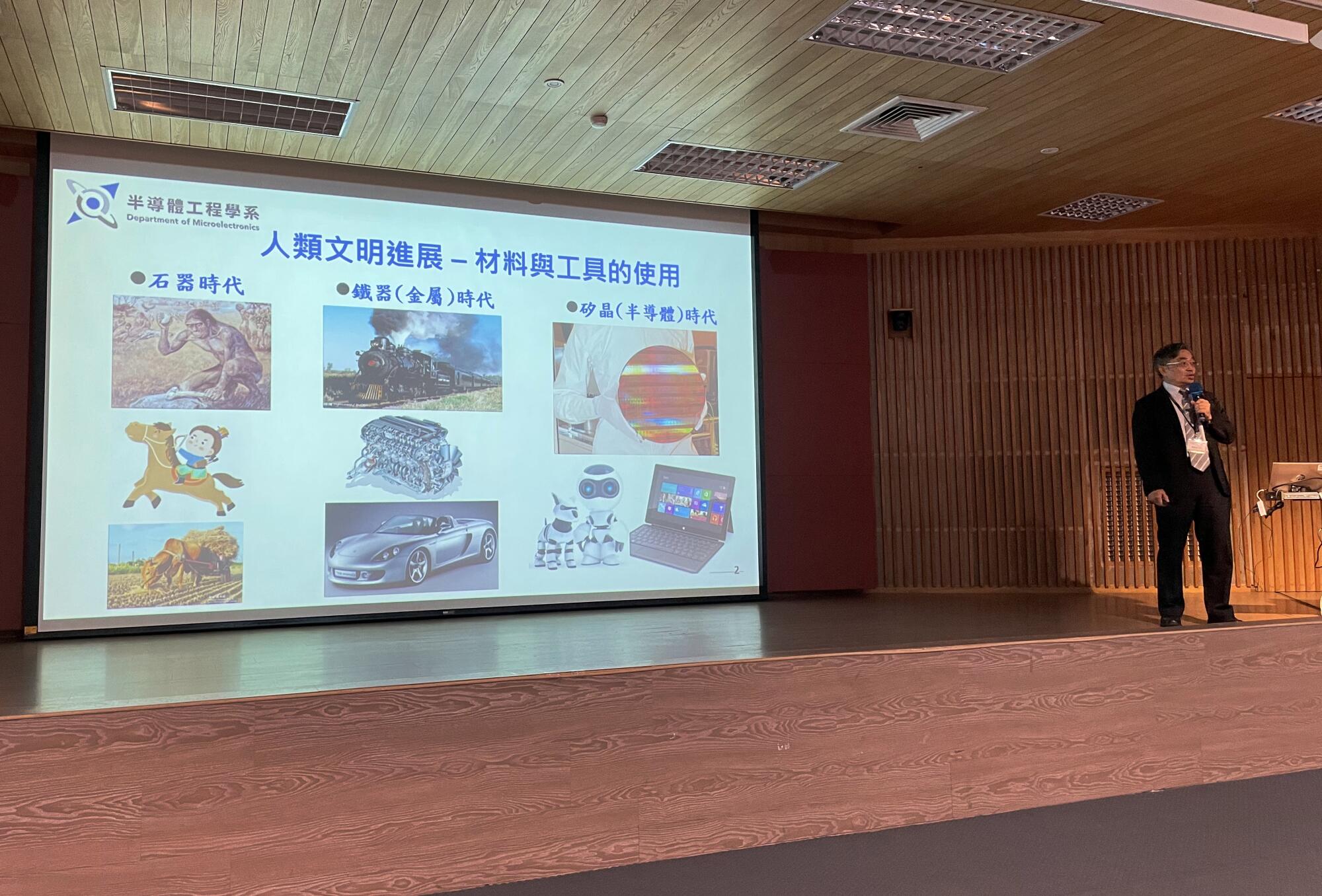

Morris Ker, the chair of the microelectronics department at NYCU, gives a presentation on why students should join the semiconductor industry.

Morris Ker, the chair of the microelectronics department at NYCU, gives a presentation on why students should join the semiconductor industry.

Seeking to maintain Taiwan’s status as the chip-making capital of the world, the government and several corporations here helped the university — known as NYCU — create the microelectronics department last year to fast-track students into industry jobs. Now the department was recruiting its inaugural class.

Wu Min-han, 20, who sat in the front row with his mother, didn’t need much convincing.

He had first applied to college to major in mathematics, but dropped out after he lost interest in the subject. Then he read about the new microelectronics program and decided to apply. He’s waiting to hear back.

“This department could have a pretty positive impact on my future career prospects,” he said.

Others were torn.

Lian Yu-yan, 18, said that while the new department seems impressive, she’s also interested in majoring in mechanical engineering and photonics. She hopes to find a high-paid tech job after graduating from college, but wants to keep her options open.

Prospective students for a new microelectronics department at NYCU take an entrance exam.

Prospective students for a new microelectronics department at NYCU take an entrance exam.

Her father, who accompanied her to the event, has worked in the semiconductor industry and sees high growth potential with the evolution of AI. However, that hasn’t done much to persuade his daughter.

“You can’t control Gen Z,” he said with a laugh and a shrug.

Many prospective students competing for the 65 slots in next semester’s program listed salary and job stability among their top considerations. In Taiwan, there are few industries that can compete with semiconductors on pay and prestige.

As the rise of electric vehicles, artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies demand more semiconductors, many nations are making chip self-sufficiency a top priority.

In the U.S., Europe and Asia, governments have announced more than $316 billion in tax incentives for the semiconductor industry since 2021, according to Semiconductor Industry Assn. and the Boston Consulting Group.

A May report by those organizations projected that private companies will spend an additional $2.3 trillion through 2032 to build more facilities that make semiconductors, also known as fabrication plants, or fabs.

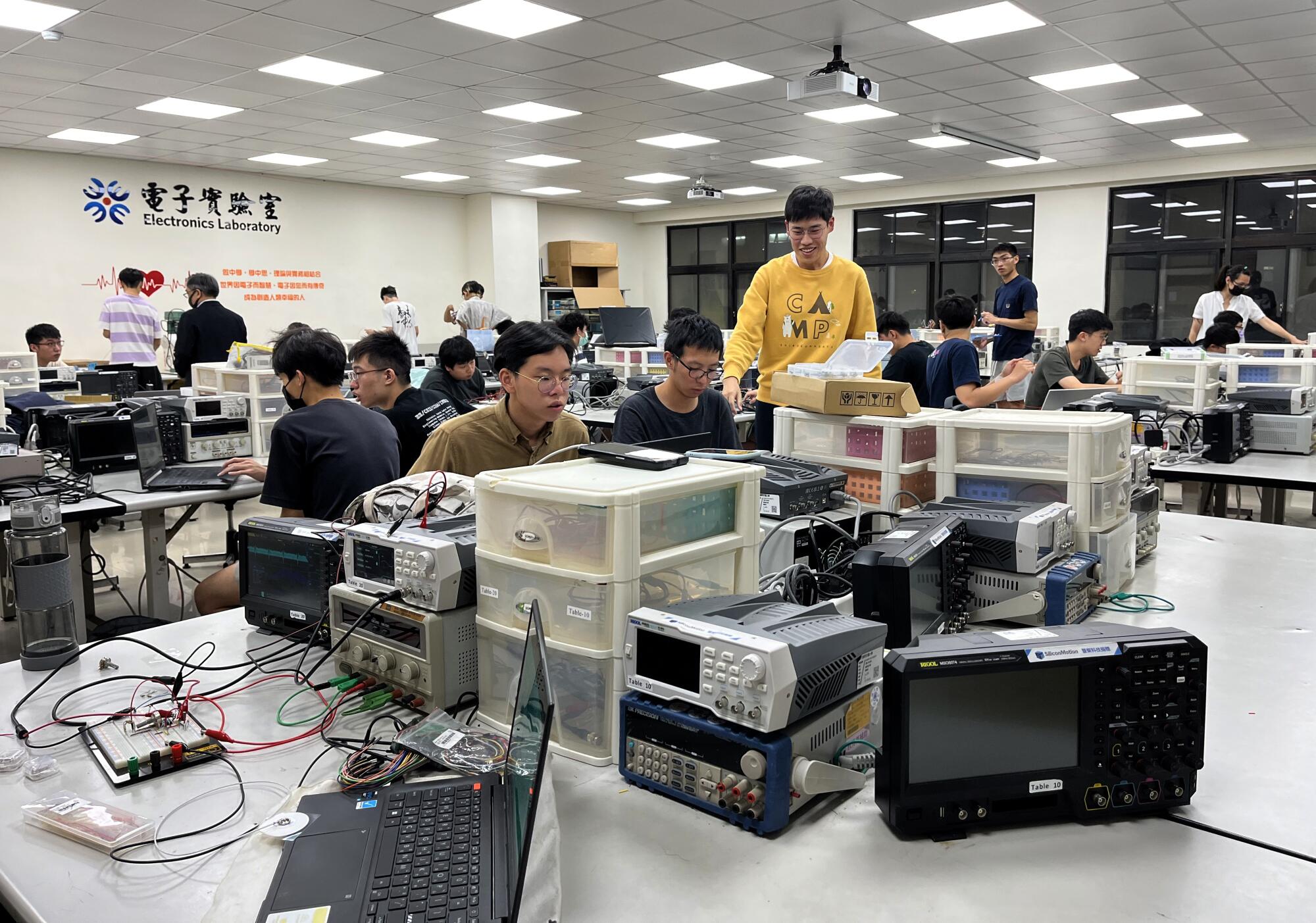

NYCU students work on building ECG heart monitors in Thursday evening lab.

NYCU students work on building ECG heart monitors in Thursday evening lab.

Meanwhile, the expansion of chip-making capabilities is exacerbating another shortage: in the people trained to make them.

As the global battle for talent heats up and Taiwan loses manufacturing market share, the island has even more incentive to cultivate its next generation of workers.

Known as Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” the semiconductor industry is considered so critical to the global economy that it could deter Beijing, which lays claim to the island democracy, from launching a military assault. Taiwanese often refer to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the world’s largest chipmaker and a major Apple supplier, as the “sacred mountain protecting the nation.”

In his presentation, Ker gave another example of the industry’s indispensability. When Taiwan’s worst earthquake in a quarter-century hit in April, factory workers were evacuated but quickly returned — a sign, Ker said, of the manufacturing hub’s resilience.

But to Su Xin-zheng, a second-year engineering student at NYCU, the natural disaster response was representative of the drudgery required to keep churning out so many of the world’s chips.

Su Xin-zheng, a second-year student, works on his final project in electronics engineering lab.

Su Xin-zheng, a second-year student, works on his final project in electronics engineering lab.

“People are always on call,” said Su, who added that he would prioritize having leisure time over a hefty salary. “We saw that they all went back in to protect the machines.”

Industry veterans evoke brutal hours and sacrifice when they describe how Taiwan built its semiconductor industry from the ground up. With black humor they speak, metaphorically, of ruining their livers by working through the night.

They fear that the younger generation is less inclined to such punishing work.

In particular, the growing emphasis on work-life balance is eroding interest in jobs at the fabrication plants that Taiwan and TSMC are known for.

For the past two years, labor demand in manufacturing has exceeded that of other parts of the chip-making process, such as designing the circuit boards or packaging them after they are made, according to the local recruitment platform 104 Job Bank. Engineering students enrolled at NYCU said such jobs seemed draining, with lower pay than research or design positions.

Ting Cheng-wei, 23, frequents anonymous online forums to learn more about the salaries and job descriptions at different companies. That’s how he knows that manufacturing positions, which require full-body suits to guard against contamination and 12-hour shifts on two-day rotations, don’t appeal to him.

Students attend a recruitment event for a program created to train the next generation of semiconductor workers.

Students attend a recruitment event for a program created to train the next generation of semiconductor workers.

“Working in the fab seems like working as a laborer,” said Ting, a master’s student and teaching assistant at the university. “Why would I work at a fab when I can sit in an office with higher pay?”

He speculated that job shortages at semiconductor plants could be solved by simply offering more money.

That would be enough for 19-year-old Wei Yu-han, who was ambivalent about semiconductors after her first year studying mechanical engineering. After visiting a fab on a school trip, she thought the work seemed straightforward and well-paid.

“I probably just brainwashed myself into liking it,” she said. “I can give up my freedom for money.”

At the end of the introductory seminar, all students in attendance took a short entrance exam as part of their applications. Still, enrollment in the new department is restricted by another squeeze on human resources — Ker added that the school is desperately looking to hire more semiconductor teachers as well.

Special correspondent Xin-yun Wu in Taipei contributed to this report.

Jackie Chiang remembers when her father-in-law was gentle and kind, taking his grandkids to school and peeling cooked shrimp for her at the dinner table.

These days, he stews silently in front of the television, convinced by the political commentators he watches that if Taiwan’s ruling party wins another presidential term, the consequence will be war — and the U.S. won’t lift a finger to stop it.

“You’re going to die, your kids are going to die, my kids are going to die, we’re all going to die. Why do you want to do that?” Chiang, who lives in the northwestern Taiwanese city of Taoyuan, quoted her father-in-law and other relatives as saying.

The fear that the Democratic Progressive Party, or DPP, along with the U.S., is propelling this self-ruled island closer to combat has become a common refrain ahead of Taiwan’s presidential election Saturday. It’s also one of the narratives that mainland China has propagated in recent months through state media, fake internet accounts and Taiwanese commentators in a widespread and increasingly sophisticated disinformation campaign, independent researchers say.

Vice President Lai Ching-te, who is running for president, front left, rides in a campaign motorcade in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, on Monday.

Vice President Lai Ching-te, who is running for president, front left, rides in a campaign motorcade in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, on Monday.

On Line, a popular messaging app in Taiwan, Chiang’s group chats have been overrun with such claims. Since the middle of last year, many of the forwarded messages have featured grim images of war-torn Ukraine and warned of the possibility of a similar conflict at home. Some posts have been lifted directly from mainland Chinese platforms such as short-video apps Douyin, which is owned by the same parent company as TikTok, and Bilibili.

“Vote for the DPP and the young will go to war,” declares the caption on one photo showing tanks and soldiers. “The people need to wake up. Only you can save your own lives.”

Chiang’s in-laws stopped sending anti-DPP photos and articles to the family group chat after her brother-in-law began responding with fact checks, but she suspects their news sources haven’t changed.

“They receive the fake news every single day,” said Chiang, 51, who teaches at a test prep center. “It’s become really extreme.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s determination to claim sovereignty over Taiwan by whatever means necessary makes the island of 23 million one of the biggest targets of foreign disinformation in the world, according to V-Dem, a Swedish research institute.

Chinese officials have accused the front-runner in Saturday’s election, Vice President Lai Ching-te of the DPP, of making “separatist” remarks and driving Taiwan to the brink of war. Beijing has refused to engage with current President Tsai Ing-wen, who has strengthened ties with the U.S. during her eight years in office.

A woman looks at a social media post on her phone.

A woman looks at a social media post on her phone.

Both Hou Yu-ih of the opposition Kuomintang, or KMT, and third-party candidate Ko Wen-je of the Taiwan People’s Party, or TPP, espouse friendlier attitudes toward China, and would be a welcome change for Beijing.

According to an August report by the Taiwan Information Environment Research Center, which tracks disinformation, official and private Chinese actors have helped spread stories that portray the U.S. as anything from a weak ally to an active conspirator in a plot to hasten Taiwan’s demise.

Chinese trolls have since broadened their critiques of the ruling DPP, according to Taiwan-based research organization AI Labs. It identified several other narratives pushed by Chinese actors last month, including the economic fallout of disrupted trade with China, the alleged erasure of Chinese culture in Taiwanese education and claims that Lai illegally expanded his family home.

Analysts said that in previous Taiwanese elections, Chinese attempts to spread disinformation were more outlandish and easily identified, marked by telltale mainland jargon and IP addresses. This time, the efforts are subtler, focusing on magnifying existing anxieties, such as government corruption and shortages of eggs, power and labor.

“What they want to amplify are real issues in Taiwan,” said Austin Wang, an assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who studies disinformation in the U.S. and Taiwan. “Their strategy has become more skilled and more long-term.”

Aided by advancements in artificial intelligence, that strategy has blurred the lines between routine political mudslinging and targeted operations meant to influence voter behavior.

The KMT, which favors warmer relations with China, has frequently attacked the DPP for pushing Taiwan toward war. Some Taiwanese media outlets have owners with business ties in mainland China, and often publish stories that echo opinions from Beijing.

“If someone is pro-China, that is a valid political stance. But at what point does the government say that this is pushing the boundaries of what constitutes free speech?” said Lev Nachman, a political science professor at National Chengchi University in Taipei. “That balance is incredibly difficult to find in Taiwan.”

Hou Yu-ih, center right, the presidential candidate of Taiwan’s main opposition Kuomintang party, visits the Sanhe Market during a campaign stop in Kaohsiung on Wednesday.

Hou Yu-ih, center right, the presidential candidate of Taiwan’s main opposition Kuomintang party, visits the Sanhe Market during a campaign stop in Kaohsiung on Wednesday.

In June, Tsai, the outgoing president, warned that large-scale disinformation campaigns meant to undermine democracy are one of the biggest challenges facing Taiwan. She said the government needs to work with civil society and fact-checking organizations to educate the public on misinformation.

Spokespeople for the KMT and the TPP said that while some disinformation likely comes from China, most of it originates domestically and from political rivals.

The proliferation of dubious content in Taiwan is a symptom of widespread mistrust in its mainstream media, which often pursue sensationalism and are politically biased. After martial law was lifted in 1987, rapid expansion of the industry in such a small market led to hypercompetition that spurred outlets to prioritize readership and viewership over accuracy.

While Taiwan ranked first in Asia in press freedom last year according to Reporters Without Borders, a 2022 study from the Reuters Institute and University of Oxford showed that only 27% of respondents trusted local media — the lowest proportion in the Asia-Pacific region.

Many Taiwanese have turned instead to political commentators and online influencers, some of whose claims and arguments align with Beijing’s. That’s increased concerns that China is using local personalities to advance propaganda and even paying them for their services.

“Things that come out of the voices of Taiwanese are going to be more effective,” said Tim Niven, research lead at DoubleThink Lab, a Taipei-based nonprofit that studies disinformation. “If you have an entanglement of orchestrated action from foreign states and authentic organic local action, then I don’t think anyone has a clue on what should be done about that.”

Lee Yi-hsiu, a political commentator known as History Bro, prepares for a livestream broadcast.

Lee Yi-hsiu, a political commentator known as History Bro, prepares for a livestream broadcast.

Lee Yi-hsiu, a political commentator known to his 268,000 YouTube followers as History Bro, said he has been asked by foreign media whether the Chinese Communist Party has paid him to spread pro-KMT opinions. His great-aunt, a fervent DPP supporter, once called him in a rage, demanding to know why he was taking money from Beijing.

He also said the Ministry of Justice Investigations Bureau paid him a visit to ask the same question. The ministry says it has no record of any contact with or investigation into Lee.

Regardless, Lee denies any payments from China, describing his content as too moderate for him to make his living as an influencer. He said he fact-checks as much as possible and studies topics for hours before going live with his commentary.

“Accurate information is not necessarily going to bring in traffic,” said Lee. “Conspiracy theories, rumors, news leaks, populism — this will bring you lots of traffic. But I think that’s temporary.”

Among the more lurid material that has found its way into teacher Chiang’s group chats is a video showing marching soldiers and blurred corpses on the battlefield in Ukraine.

“No matter how many funds or weapons the U.S. or Europe provide, the hardest thing for Ukraine to bear is the cost of human lives,” a narrator intones, the warning for Taiwan implicit.

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox. You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But if the Ukraine war helped cement her in-laws’ animosity toward the DPP and the U.S., it’s had the opposite effect on Chiang herself.

After Russia invaded its neighbor, she started seeking out more political news, using keywords such as “war” and “Communist Party attacking Taiwan in 2027.” The majority of results ended up coming from the same pro-China media that her in-laws read, outlets that she’s reluctant to trust.

She also worries about the beliefs of younger people, many of whom support Ko, the third-party candidate. Ko and the party he founded, the TPP, have made inroads with the youth vote by posting viral videos and tapping into their economic frustrations. He has positioned himself as a middle-ground alternative to the two main parties.

But to Chiang, he represents another extreme.

“He is more hatred,” she said. “I feel like the kids hate the government. They feel like it’s not fair — they don’t have enough jobs, there are low wages, no housing. [They say:] ‘This is not fair, that is not fair, everything is not fair.’”

Chiang voted for Tsai in the last two elections, seeing her as a step toward stronger international ties. While her in-laws worry that another DPP president would provoke an attack by Beijing, Chiang is afraid that a KMT or TPP win would allow the Chinese Communist Party to exercise more control over Taiwan.